Widmann embraces dialogue of past, present

David Weininger writes about Yellow Barn's Composer in Residence Jörg Widmann for The Boston Globe:

As a teenager, Jörg Widmann hung pictures of two musical heroes on the wall of his Munich bedroom: Pierre Boulez and Miles Davis. They make an odd couple at first glance, the allegedly dogmatic serialist and ruler of the French music scene and the famously protean jazz titan who evolved by shedding styles as quickly as he adopted them.

But to Widmann, who took up the clarinet when he was 7 and began composing not long after, there was no contradiction. “I was fascinated equally by them,” he said during a recent conversation from his home in Freiburg. In Boulez, who would later become an important mentor, he heard not determinism but “the opposite — what I heard was orgasms of color and freedom of sound.” Listening to Davis and his band playing at Munich’s Philharmonie in the 1980s, Widmann said, “the incredible thing was what he did not play. The notes he did not play were so amazing.”

Widmann’s unique way of resolving seeming contradictions into something new and unexpected is more than a (very German) facet of his personality: It is perhaps the most important characteristic of his work. Widmann’s music is incontestably of this moment, music that could only be written now, and yet no other composer is so deeply engaged in a dialogue with the past, a tradition which the composer, who is the subject of an upcoming residency at the Yellow Barn music school and festival in Putney, Vt., is both a part of, and stands apart from.

He reached this point not solely through his own creations but, as importantly, through his career as a clarinetist and his constant engagement with the masterpieces of the repertoire. Earlier this month he played Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet with the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. “That’s another piece where, how can I close my doors and say, OK, now it’s time to write something completely different? But of course, it’s my obligation to do something different.

“I’m very interested in a dialogue,” he went on, “but not in a nostalgic way, looking back and saying, well, it was so nice in the past. A dialogue is not always only agreeing with each other. Sometimes it’s a questioning of the other one.”

Take Widmann’s “Hunt Quartet,” his third string quartet, whose title is a clear reference to a Mozart work of the same name. The piece opens in a healthy A major, with clear references to a famous rhythm from Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. Quickly, though, easy guideposts fall away, harmonies darken, and the music is eventually consumed by noise generated entirely by extended string techniques. The cellist becomes, at least metaphorically, the victim of the “hunt.” A tradition is not erased so much as brought to its extreme conclusion.

One might think the composer of such stuff as the quartet and the recent opera “Babylon” would be an imposing, thorny person. But Widmann, 42, is a warm and generous conversant, laughing often and almost overflowing with enthusiasm about all things musical, as if the passion that ignited him early on has never worn off. He is particularly pleased by the diversity of Yellow Barn programs — curated by artistic director Seth Knopp — since their deft mix of old and new appeals naturally to his own artistic inclination.

He also appreciates the fact that, along with well-known pieces like the “Hunt,” Knopp insisted on including some of Widmann’s more obscure works. None, probably, is more obscure than “Skelett,” a 2004 solo-percussion piece that mischievously upends the idea of a virtuoso solo display. In fact, it doesn’t even have a written score: Widmann conceived of it, he said, after realizing that after concerts, “each time, as [the rest of us] enjoy a beer or a glass of wine at the bar, the poor percussionist still has to [take apart] their percussion instruments. And it takes two hours!

“So I wanted to write a piece about that moment,” he continued, as the percussionist grows increasingly frustrated and begins to create “these sounds which you would never use in a regular piece.” Widmann paused, then added, thoughtfully, “I don’t even know if it is a piece.”

Still, he seemed delighted to have the chance to work through it with Eduardo Leandro, Yellow Barn’s percussionist. “Maybe there will be a score at the end. I’m very curious about it myself.”

What the diversity of the programs also makes clear is how varied Widmann’s output is. He is unafraid to radically change direction from work to work. Indeed, he seems driven simultaneously to use whatever materials suit his expressive purpose — tonal, atonal, lyrical, or noisy — and to avoid repeating himself. It is both freedom and obligation, a productive ambivalence that Davis, in particular, would have appreciated.

“I don’t like the idea of doing the same thing all your life, and then somebody calls it ‘style,’ ” he said with a laugh. “I have great respect — there are many people who work like that and really have a language — you hear three notes and then, ‘Well of course, that’s this and this composer’ . . . [But] even when I write a piece and I start the next one, many times it is just the opposite.

“I have two tables, and sometimes I write two contrasting pieces at the same time. When I wrote my orchestra piece ‘Lied,’ it’s a very tonal piece, a Schubert homage, on the other table there was a kind of piano-destruction piece, ‘Hallstudie,’ which is 40 minutes long. The pedal is put down all the time, and until the first normal note is played it’s 15 minutes — until then it’s wood sounds, metal sounds, piano-lid banging. Everything is in reverberation and echo.

“And to me it’s not a contradiction,” Widmann continued. “I just try not to repeat myself.”

Jörg Widmann's Composer Portrait: August 4

Complete schedule of works by Jörg Widmann: August 3 - August 8

Monday | 8:00pm

Skelett (2004)

North American Premiere

With works by Bartók, Manoury, and Schubert

Tuesday | 8:00

Air for horn solo (2005)

United States Premiere

Elf Humoresken (2007)

Skelett (2004)

Duos for violin and cello "Heidelberg edition" (2008)

Fantasie for clarinet solo (1993)

Wednesday | 8:00

Jagdquartett (2003)

With works by Adès, Mozart, Debussy, and Couperin

Thursday | 8:00

Liebeslied (2010)

North American Premiere

With works by Stravinsky, Carter, and Schoenberg

Friday | 8:00

Tränen der Musen (1993)

North American Premiere

Ikarische Klage (1999)

With works by Wood and Janáček

Saturday Matinee | 12:30

Fünf Bruchstücke (1997)

Versuch über die Fuge (2005)

With works by Dvořák and Schumann

Season Finale | 8:00

…umdüstert… (1999-2000)

With works by Donatoni, Mozart, Britten, and Harvey

Haunted by Shakespeare's witches?

Matthew Guerrieri writes for The Boston Globe:

On Tuesday, Yellow Barn presents a free concert, a thank you to the residents of the chamber music center’s hometown of Putney, Vt. The concert includes an echo of a rather grimmer homecoming: Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Trio in D (Op. 70, No. 1), called the “Ghost” Trio because of the eerie nature of its slow movement — which, it has often (if not uncontroversially) been speculated, was originally created for an operatic adaptation of William Shakespeare’s “Macbeth,” an adaptation abandoned after Beethoven’s librettist begged off the project, put off by the story’s unremitting darkness. (In 2001, Beethoven’s few sketches were fashioned into a reconstructed “Macbeth” overture by Dutch composer Albert Willem Holsbergen.)

The play’s First Folio printing included indications for a few songs — probably numbers by Robert Johnson, who also wrote music for “The Tempest”; by the 1700s, “Macbeth” was performed with incidental music so common it was called the “Famous Music,” attributed to everyone from Matthew Locke to Henry Purcell, but most likely by a singer and composer named Richard Leveridge. But Shakespeare himself specified comparatively little music in the original script. Leveridge’s contributions date from the Restoration era; even Johnson’s songs were probably interpolated only some years after the play’s premiere, for a performance at court. Apart from some brief fanfares to establish royal and martial atmosphere, “Macbeth,” it seems, was conceived as a musically austere experience.

That music for the play proliferated around its most exotic characters — Johnson’s songs and Leveridge’s settings were in service of scenes featuring the three witches — is also significant. Music was a stand-by for Elizabethan scenes of witchcraft and sorcery, with awkward dancing and sudden, reedy instrumental blasts reinforcing witches’ unearthliness and melancholic menace. It may have been a later addition, but for a lean staging of “Macbeth” to suddenly erupt into a masque-like musical number would have been discontinuous and inappropriate in all the right ways.

Over time, the witches and their music came to be a pleasurable highlight rather than a disconcerting dissonance. Joseph Addison, writing in 1711, complained of some fellow audience members who chatted throughout the rest of “Macbeth” waiting only for the witches, who they complimented as “charming creatures” — a far cry from the infernal figures who promise to “charm the air to give a sound.” The “Ghost” Trio, perhaps, preserves a hint of that sorcery, but Beethoven’s version of Macbeth’s trumpets — “Those clamorous harbingers of blood and death” — was destined to remain unwritten.

Find out about Yellow Barn's free concert for the community on Tuesday, July 28

Discovering an immersive art installation

LUMEN

An immersive interdisciplinary installation

Catherine Wagner, Artist

Thomas Kelley, Architect

Eric Nathan, Composer

Loretta Gargan, Landscape Architect

From the premiere installation of LUMEN for "Cinque Mostre: Time and Again” at the American Academy in Rome

On March 19, 2013 Pope Francis was inaugurated as the 266th Pope of the Catholic Church, signaling a crucial break from the weight of the past and an eye for a hopeful future. His first encyclical letter, Lumen Fidei (The Light of Faith), disseminated throughout the Catholic world, is infused with the overwhelming potential for humans to flourish during timorous times. He states with a modicum of severity, “[I]n the absence of light everything becomes confused; it is impossible to tell good from evil, or the road to our destination from other roads which take us in endless circles, going nowhere.”[1]

Inspired by the new Pope’s affinity for light as a metaphor for change, LUMEN aims to abstract and re-contextualize an act of spiritual contemplation. Driven by a secular regard for the Pope’s palpable sense of hope, renewal, and greater acceptance of outsiders, the installation sited in the Cryptoporticus at the American Academy in Rome incorporates a minimalist redesign of the pew, a long bench with a prayer stand typically used in a church for seating a collective. As a multimedia installation, the rows of white pews are planted with beds of thyme that invite the viewer to participate in an multisensory installation. These multiple elements are coupled with a musical score choreographed to play in dialogue with the projection of shifting light.

Upon entering the Cryptoporticus the procession begins. The white of the painted brick walls establishes a visual corridor remnant of a single-point perspective. The rows of sleek white pews, topped with thyme, glow and enliven the space to create a conversation between two and three dimensions. Looking further, the viewer’s eyes track a video of moving light as sound initiates the immersive experience. Each element of LUMEN functions individually and as part of the larger whole. Like the congregation of persons who come together to bear witness at an event, the parts sing as a group.

The minimalist design of the pew recalls the monumental shift in art, philosophy, and consciousness exemplified by modernist artists such as Donald Judd. The original design placed emphasis on several factors that include posture, close attention, and orientation towards an object-relic. Taking a utilitarian approach to form and finish, the redesigned pew’s standard elements are at once familiar and not. The traditional time worn wood of the bench that is etched in our collective memory is now given over to a pure white lacquer finish that transcends the patina of time and brings the sculpture into a contemporary context. Form and function establish the objecthood of this elegant icon, while the remembrance sparked by familiarity initiates connection to inner spirituality. While the pew remains iconic in scale and orientation, it no longer demands the observer to acknowledge any singular belief, but rather commences a new and open contemplation.

To deepen the experience, the prayer stand of the pew has been replaced with a thyme garden that initiates the first act of the immersive environment: smell. As memory is most deeply recalled through the olfactory sense, the scent of this herb is one that transcends time. As Marina Heilmeyer, author of Ancient Herbs, recounts, “What truly mattered in antiquity, however, was the scent of thyme rising from altars to please the gods. The intensity of this aroma, heightened by burning, may also account for its name, because the Greek word thymon refers not only to this plant but also to heart, flame, vital energy, passion, and smoke.”[2]

The video is a six-minute meditative loop of gradually shiftng light. The camera remains absolutely motionless as a slight, illuminated line maps where two walls meet. It comes together; it separates; it vanishes only to reappear anew. The ceiling of the room can be seen as an almost-black joint forming a room that appears to be at once approaching and receding. The slightest shift of magnitude in the band of light throws the room jumping between shades of gray. As this band moves back and forth, the grays of the walls seem to react in their own volition, flowing between deep, cool and light hues. The pacing is hypnotic on a level akin to watching the sun rise or set; one cannot look away. Like that ritual of the constancy of the Earth’s rotation, we are reminded of the permanence of light. In the last seconds, as the source of illumination closes with comparative rapidity, something unexpected happens in the wake of the receding light: the room begins to brighten. The deep shadows that were cast in the wake of the blast of light soften and give way to a glow as the last hint of brightness flits in a line.

The accompanying composition brings to the installation a haunting suite of strings and ambient shifts that aims to invite the viewer to become a participatory member engaged through mind and spirit. Listening to the light slide back and forth is at once both calming and exhilarating—sitting through multiple loop-cycles, one cannot help but create narratives guided by mystery and change. The unknown is presented, explored, and left for perpetual contemplation by the viewer.

LUMEN presents an invitation: to share in a space that transcends history and physicality. The vast experiential differences between this installation and the rites it draws upon are left to the participant. The interaction between the viewer and the installation begs contemplation without the imposition of a specified authority. Through an interdisciplinary approach to installation, LUMEN revaluates contemporary spirituality in the production of culture.

—Peter Cochrane

[2] Marina Heilmeyer from Ancient Herbs. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.

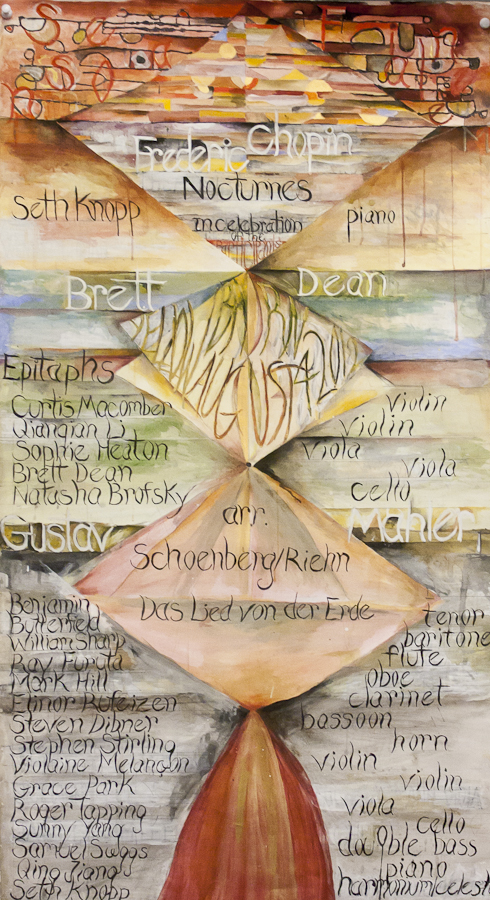

Yellow Barn Wall Programs

Wall programs have been a tradition since the first Yellow Barn concerts, when programs were not printed but rather posted on the wall for all to see. In 1998, artists Bill Kelly and Michele Burgess transformed wall programs into works of art, inviting musicians, staff members, and Yellow Barn family members to create hundreds of wall programs over the ensuing decades.

Michele and I have been making wall programs with Yellow Barn for 17 years. We have watched musicians grow wiser, more finely tuned. We have made posters with their children who have grown up to be amazing young people. In other words, there is a history here. The musical discoveries and visual ones are never ending. Wall programs have stretched my work—some have turned into paintings. Some have been torn up in disgust—a parallel to consider. There have been performances I still play in my head. There have been many things I will never forget. Artists live by their prior convictions. History is such a funny thing. In the bigger picture are all the little gestures, the moves, so to speak. Yellow Barn is seriously one of the most profound things we have been involved in.

—Bill Kelly

Improvisation for all

David Weininger writes about Battle Trance's performance for The Boston Globe:

Travis Laplante was 10 when he made what would turn out to be one of the most important decisions of his life. He was a fourth-grader in Woodstock, Vt., and it was time to choose an instrument to play in the school band. He didn’t know what he wanted to play, though he’d thought about the drums since that was obviously the coolest option. So he asked his mother — not, as far as he knew, a terribly musical person.

“I remember her looking at me in the eyes and saying, ‘You know, Travis, I just really love the saxophone,’ ” Laplante says in a phone conversation. “There was something about that — I can’t really talk about it in terms of logic, but I said, OK, Mom, I’m going to play the saxophone.”

It turned out to be an auspicious choice, since Laplante, 32, has built a career as a tenor saxophonist whose musical acuity encompasses both avant-garde classical compositions and free jazz. Yet he seems to move forward, open up new projects, less by conscious choice than by a kind of intuition — almost as if someone else were making the decision through him.

Take the formation of Battle Trance, the saxophone quartet that will be performing at the Yellow Barn Music School and Festival in Brattleboro on Friday. Late in 2012, Laplante was working a part-time job when he had what he calls “this very strong feeling” that he had to form a band with three other tenor players: Matthew Nelson, Jeremy Viner, and Patrick Breiner.

A quartet of tenor saxophonists would be unusual enough, but for Laplante it wasn’t about the specific instrumentation — it was those three people. This despite the fact that while he “sort of” knew Breiner from New School University, which they had both attended, he had met the other two only in passing. He had no idea what they were like or what their musical proclivities were. But they were, unquestionably, the guys for the band.

“Yeah, pretty much,” Laplante says, laughing, when the basic outlines of this unlikely scenario are repeated back to him. Even he didn’t seem to quite believe it. “There was a side of me that was like, You’ve got to be kidding me – a quartet of tenor saxophones? I’d never thought of that before. It was quite . . . unusual.”

But when he tracked down the other three by e-mail and told them what he wanted to do, they all responded quickly and affirmatively. When they first got together, Laplante didn’t have any music written, nor did he even know precisely what he wanted the band to do.

“I just wanted to get everyone in the room and see what would happen,” he says. “And we ended up mostly talking, getting to know each other, but in a very intimate, vulnerable way where I wanted to express to them what matters to me, in life and in music, and to just have an open conversation to make sure that that resonance, that feeling I had at work, was really true.”

That rehearsal ended with the four of them holding a unison B-flat, the lowest note on the instrument, “for I don’t know how long. A half-hour, maybe 45 minutes. Just to really be together, in sound.” Not long after that, Laplante began writing “Palace of Wind,” the 45-minute work that pretty much forms the entirety of Battle Trance’s repertoire.

Or, as he puts it, “the piece started writing itself.” Almost nothing was written down; Laplante transmitted the music orally to the other three musicians, who memorized it. (A notated score was prepared later.) It was, Laplante says, “the most effortless process I’ve had writing music. . . . It felt like we were on completely fertile ground, and that there was this freshness, or this innocence, to almost everything we were playing.”

“Effortless” is not the word that comes to mind when listening to “Palace of Wind.” The work’s technical and expressive range is astounding: eerie chords with multiphonics, driving repeated notes, screaming melodic lines, and gripping moments of calm. The waves of sound are relentless, as there are almost no breaks in the piece even for the saxophonists to grab a breath; they use a technique known as circular breathing to sustain the piece over its duration.

It may sound forbidding, but when “Palace of Wind” was released last year on the New Amsterdam label, it won a host of plaudits, including mentions for best album of the year. One of the most insightful reviews came from Mission of Burma’s Roger Miller, who wrote about the disc for the music website The Talkhouse (www.thetalkhouse.com): “[T]his is Battle Trance’s first album and they are definitely onto something. . . . There is so much energy here. The newness of ‘Palace of Wind’ lies in the order and structure that contains that energy, and allows it to burst forth into your mind’s sky.”

In addition to performing “Palace of Wind,” Battle Trance will also work with musicians in Yellow Barn’s Young Artists Program on improvisation. It’s tempting to view this as a different side of Laplante’s artistic persona, one that runs through free jazz and the later John Coltrane records he devoured as a teenager. “But the fact is, I believe that everyone is born an improviser,” he says. “That’s something that as we go along in life sometimes gets a little bit closed off.” Part of what he wants to do with the students is “to relieve a certain fear that seems to have been instilled upon many classically trained musicians,” who view improvisation as foreign ground.

“A lot of it is equally about unlearning certain things,” he continues. “Like right now, as a musician, I feel like I have to unlearn as many things as I have to learn — actually undo particular conditioning and habits that I have, particular patterns of my mind, when improvising or playing music in general. So I’m hoping that some of that can be passed on — that it’s actually possible to play your dream. That is possible.”

Palace of Wind

Since many of the techniques used in Palace of Wind are nearly impossible to notate in traditional form, the piece was transmitted via oral tradition. The rehearsals were much like martial arts training: intricate sounds were rigorously copied and repeated by the ensemble members until they perfected the techniques. Many hours were spent building the sheer strength required to sustain continuous circular breathing for extended periods. Likewise, a steady focus on physicality was required to repeat rapid note patterns for long periods without sacrificing speed. Palace of Wind is such a demanding composition that there is a high risk of physically burning out before the piece concludes, as once it begins there is no opportunity for rest or even a quick drink of water. There was also extensive training in dissolving the distinct individual identities of the players into the greater collective sound: The band did various long-tone exercises, similar to group meditation, the purpose being to blend together into one sound, so that the origin of the collective sound's components is completely impossible to discern - even by the members of the ensemble.

Palace of Wind does embrace both the cerebral nature of composition and the visceral act of performance, but immediately locates itself, the musicians, and the audience in a purely spiritual space. It is a new kind of music and therefore modern, and yet it's absolutely primordial, the transformative act of human beings blowing air through tubes and producing something timeless.

"Mesmerizing...a floating tapestry of fascinating textures made up of tiny musical motifs, and a music that throbs with tension between stillness and agitation, density and light."—The New York Times

Read a conversation with Travis Laplante

Find out what others are saying about Battle Trance and Palace of Wind at Travis Laplante's website